Italian physician Santorio Santorio is the father of the thermometer, inventing the heat-measuring device way back in the early 1600s. About a hundred years later, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (yes, the inventor of the heat-measuring scale) improved on Santorio’s thermoscope by coming up with its modern-day design — the mercury-based thermometer.

Even then, 400 years ago, they noticed something significant and quantifiable: cities were much warmer than the surrounding areas.

The Urban Heat Island Effect (UHIE) had been discovered.

Fast-forward a near half-century to present day, and the UHIE hasn’t gone away, but it has become more pronounced.

As cities have become more concrete and dense, eliminating any natural cooling vegetation, temperatures have sharply risen with surfaces like asphalt roofs and roads absorbing the heat.

The Environmental Protection Agency has data showing temperatures are seven and five degrees (F) higher in the day and night, respectively, in urban areas than the outlying areas. And if you’re in a poor neighbourhood, where trees are few, the difference can be as high as an astonishing 20 degrees.

This isn’t just about comfort — it’s about life and death. Heat waves are the No. 1 weather killer in the world. Not floods, fires, hurricanes or earthquakes, but heat.

And it’s not just from heat stroke, but those with underlying conditions like asthma or lung disease having their symptoms aggravated by the higher temperatures.

And with the number of high-heat days expected to double in the next 20 years, we can expect that death toll to skyrocket.

Singapore is held up as the model of what a city shouldn’t do — and what one should do. The island was once covered in dense, tropical lowland forests in the 19th century before industrialization brought upon by the nation’s newfound status as integral trading port meant that 90 per cent of it was razed to the ground.

And with the island heating up almost twice as fast as the rest of the world, experts there for decades have been trying to mitigate the UHIE.

New skyscrapers are only permitted in certain areas, in order to encourage better wind flow; green roofs and vegetations are being incorporated in construction, and the One Million Tree drive has turned Singapore into the “greenest city in the world.”

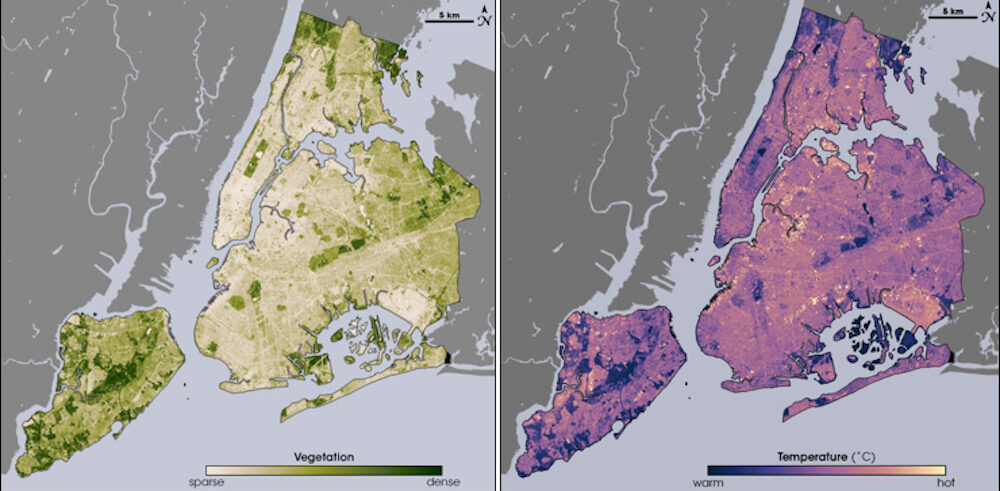

The amount of vegetation has a direct correlation to the temperature in cities; the more green, the cooler it is.

Another recent innovation is the invention of a coating that the producers say reflects up to 98.1 percent of sunlight and sheds surface infrared heat. In Singapore, air conditioning units are a huge part of the problem.

Aside from the massive energy footprint the units require, there is a compounded heat effect that can be intense enough to affect the local microclimate. As hot air is expelled from lower-mounted units, it is ingested by those higher up, which then vent even hotter air. The process is repeated all the way to the top floors of building towers, where hot plumes of air are ejected into the atmosphere.

The fossil fuel cost of fuelling these A/C units is staggering, and is UHIE’s main contributor to global warming, not the localized heat increases.

Real-time speed of global fossil fuel CO₂ emissions (each box is 10 tonnes of CO₂).

Jaw-dropping #dataviz by @neilrkaye.https://t.co/6s6SIGwJ9g pic.twitter.com/jRMxYs4ev7

— Randy Olson (@randal_olson) September 17, 2019

This animation shows the average, maximum, and minimum temperature anomalies for each state in the United States. It’s alarming! (Created by Antti Lipponen, @anttilip) #Climate pic.twitter.com/0FTLy5QGCp

— Climate Reality (@ClimateReality) May 29, 2019

Reducing the level of fossil fuel expulsion will slow the rise of global temperatures, and here are a few ways we can help reduce the UHIE’s contribution to that:

— Use reflective paint or similar coatings that decrease surface temperatures.

— Smart city planning; tall buildings block wind. Allow construction of new ones only in certain spots. Reducing ‘urban canyons’ or those areas where tall city buildings can trap radiant heat is another tactic.

— Trees, trees and more trees. Plant more trees, especially in poorer neighbourhoods where they were removed in early decades.

— Grass, grass, and maybe some bushes. Green roofs have many positive effects, from insulating properties to sound mitigation to air pollution reduction.